Guest Piece by aFewSteps intern Matt Chevalier

(SOURCE: LancasterOnline)

(SOURCE: LancasterOnline) As an intern for the environmental group aFewSteps, I have learned that most people in the borough of Swarthmore see their area as a bastion of progressiveness. They pride themselves on tolerance for differences and commitment to social justice.

However, every time they throw out garbage, they are complicit in a racial injustice that has been going on for decades.

We cannot help but produce some waste; it is all part of being human. But what really happens to our garbage? Who is responsible for properly disposing of it? How is it distributed? Who really carries the environmental burden?

However, every time they throw out garbage, they are complicit in a racial injustice that has been going on for decades.

We cannot help but produce some waste; it is all part of being human. But what really happens to our garbage? Who is responsible for properly disposing of it? How is it distributed? Who really carries the environmental burden?

Here in Delaware County, most of our trash finds its way to the Delaware Valley Resource Recovery Facility, the largest incinerator in the United States, which is owned and operated by Covanta Energy.

How about municipal wastewater? Where do your sewer systems lead to? For Delaware County, wastewater is processed at the Delaware County Regional Water Quality Control Authority, which is also located in Chester.

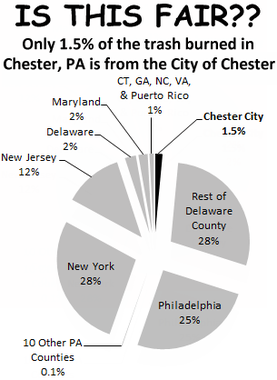

What about out-of-state waste? Some counties are just not capable of disposing their garbage on their own land, so the only option is to transport trash elsewhere. Consistently, waste transfer companies from states as far away as Virginia choose to transport their garbage to be burned in Chester. In fact, only 30% of the trash burned in Chester is actually from Delaware County.

Notice a pattern?

When Chester suffered an enormous loss in industry between1950 and 1980, the city’s economy was pushed to the verge of collapsing. And while most of the city’s wealthier residents were able to simply pick up and leave, the urban poor, the majority of whom were African-American workers and families, had no choice but to stay. This sudden population decline and rise in poverty levels, along with the corrupt politicians that took power soon after, made Chester a prime location for heavily-polluting plants and facilities, many of which had little to no pollution controls.

How about municipal wastewater? Where do your sewer systems lead to? For Delaware County, wastewater is processed at the Delaware County Regional Water Quality Control Authority, which is also located in Chester.

What about out-of-state waste? Some counties are just not capable of disposing their garbage on their own land, so the only option is to transport trash elsewhere. Consistently, waste transfer companies from states as far away as Virginia choose to transport their garbage to be burned in Chester. In fact, only 30% of the trash burned in Chester is actually from Delaware County.

Notice a pattern?

When Chester suffered an enormous loss in industry between1950 and 1980, the city’s economy was pushed to the verge of collapsing. And while most of the city’s wealthier residents were able to simply pick up and leave, the urban poor, the majority of whom were African-American workers and families, had no choice but to stay. This sudden population decline and rise in poverty levels, along with the corrupt politicians that took power soon after, made Chester a prime location for heavily-polluting plants and facilities, many of which had little to no pollution controls.

Everyone deserves the right to breathe clean air, drink clean water, and live without worry of illness or property damage due to pollution. The protection of people’s right to a healthy environment is a facet of social justice known as environmental justice.

Even though residents of Chester make up for only 8 percent of the total county population, their city contains 60 percent of all the county’s waste facilities. And Chester is not the only such case; all across the nation, communities of color are being disproportionately targeted by polluters.

Even though residents of Chester make up for only 8 percent of the total county population, their city contains 60 percent of all the county’s waste facilities. And Chester is not the only such case; all across the nation, communities of color are being disproportionately targeted by polluters.

(SOURCE: http://www.ejnet.org/chester/)

(SOURCE: http://www.ejnet.org/chester/) Is this justice? Is this equality? Why is it that some can have clean air and others can’t? Why is it okay that their city has lung cancer rates that are 60 percent higher than anywhere else in Delaware County? Are only certain children worthy of protection from environmental hazards? Why is it acceptable that minority communities suffer so that richer, whiter communities do not have to?

All is not lost, however; Chester is fighting back. From 1992 until 2001, the Chester Residents Concerned for Quality Living (CRCQL), a grassroots organization, has been launching campaigns against polluters. The CRCGL organized protests and public hearings, with the mission of equipping residents with the means to coordinate efforts to fight pollution.

One of their biggest accomplishments was in 1996, when the CRCQL sued Pennsylvania’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) for environmental racism after it granted Soil Reclamation Services (SRS) permission to set up a plant in Chester. The lawsuit made it all the way to the United States Supreme Court, garnering national attention as the first environmental racism lawsuit in U. S. history. In the end, the community successfully prevented the SRS plant from being built in their neighborhoods.

All is not lost, however; Chester is fighting back. From 1992 until 2001, the Chester Residents Concerned for Quality Living (CRCQL), a grassroots organization, has been launching campaigns against polluters. The CRCGL organized protests and public hearings, with the mission of equipping residents with the means to coordinate efforts to fight pollution.

One of their biggest accomplishments was in 1996, when the CRCQL sued Pennsylvania’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) for environmental racism after it granted Soil Reclamation Services (SRS) permission to set up a plant in Chester. The lawsuit made it all the way to the United States Supreme Court, garnering national attention as the first environmental racism lawsuit in U. S. history. In the end, the community successfully prevented the SRS plant from being built in their neighborhoods.

(SOURCE: http://www.ejnet.org/chester/)

(SOURCE: http://www.ejnet.org/chester/) Since then, the CRCQL, which has since reorganized into the Chester Environmental Justice group, has defeated the building of a construction and demolition waste-transfer system and a tire-burning plant, and have worked to improve the pollution control standards in their community.

Even with all the progress the people of Chester have made the past two decades, there remains much more work to be done. Recently, Covanta signed a contract with New York City and submitted a proposal to Chester City Council to transport about 15 million tons of trash to Chester over the next 30 years. On August 13, the Chester City Council passed Covanta’s application to build two new buildings to house these trash trains, despite the urging of several community activists and the City Planning Commission to reject the plan.

Environmental racism is one of the many ways in which racism pervades our society to this day. Experts have shown time and again that minority communities are being disproportionately targeted with environmental burdens. Communities, in turn, have shown that environmental racism is something that can be fought, through organization and solidarity.

You can do your part by educating yourself and your friends. Read through Chester Environmental Justice group’s website (http://www.ejnet.org/chester/) to learn more about the CRCQL’s efforts and how to get involved. Pay attention to news stories and zoning policies in your area and across the nation. Stand with communities everywhere who are rising up and fighting pollution. Together, we can help make our environment cleaner and healthier for all people to enjoy.

Matt Chevalier is a rising junior at Temple University majoring in English. They are a member of Temple Students for Environmental Action and the Temple Area Feminist Collective.

Even with all the progress the people of Chester have made the past two decades, there remains much more work to be done. Recently, Covanta signed a contract with New York City and submitted a proposal to Chester City Council to transport about 15 million tons of trash to Chester over the next 30 years. On August 13, the Chester City Council passed Covanta’s application to build two new buildings to house these trash trains, despite the urging of several community activists and the City Planning Commission to reject the plan.

Environmental racism is one of the many ways in which racism pervades our society to this day. Experts have shown time and again that minority communities are being disproportionately targeted with environmental burdens. Communities, in turn, have shown that environmental racism is something that can be fought, through organization and solidarity.

You can do your part by educating yourself and your friends. Read through Chester Environmental Justice group’s website (http://www.ejnet.org/chester/) to learn more about the CRCQL’s efforts and how to get involved. Pay attention to news stories and zoning policies in your area and across the nation. Stand with communities everywhere who are rising up and fighting pollution. Together, we can help make our environment cleaner and healthier for all people to enjoy.

Matt Chevalier is a rising junior at Temple University majoring in English. They are a member of Temple Students for Environmental Action and the Temple Area Feminist Collective.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed